By Al Sears, MD

Endurance running and aerobics are NOT the best way to get fit

I’ve written to you many times about how endurance running is bad for your heart and lungs.

Today I want to tell you about how it affects your muscles.

Skeletal muscles are the ones you can see, and the ones you exercise when you move. They attach to your bones via tendons and power up your whole body.

Strong skeletal muscles fill you with strength and potential. They give you the feeling of confidence and they ensure you stay mobile and independent.

And the strength of your leg muscles plays a lead role in how long you’ll live.

A study from the University of Pittsburgh followed nearly 2,300 people for five years. It found that low muscle strength in your quadriceps made you 51 percent more likely to die.1

Two other studies found that leg strength offsets the risk of death for people with certain illnesses.

In the first study, the only two things that predicted death were age and quadriceps muscle strength.2

The second found that for people who had congestive heart problems, the ones with the weakest quadriceps muscles were 13 times more likely to die within two years.3

Your muscles are made up of different kinds of fibers that you use for different purposes.

Traditional cardio or aerobic exercise uses the smaller muscle fibers because they are more oxygen efficient, and don’t tire as easily as large muscle fibers.

If you continue to do moderate aerobic workouts, your body will ignore the larger fibers, leaving them weak.

One study even found that long-duration running makes your leg muscles deteriorate.

Take a look at this new study that followed endurance runners during the Trans-Europe Foot Race in 2009.

They had a mobile MRI machine scan these endurance athletes every day. When the race was over, instead of the runners’ muscles getting stronger, their leg muscles had degenerated.

They had lost 7 percent of their muscle mass.4

This is why doing aerobics and running for hours on end is not a good idea.

The solution to building stronger muscles that will keep you going for years to come is my PACE program.

It’s why I write to you about it as often as I can.

With PACE, you challenge your cardiopulmonary peak a little bit at a time. Your body will then respond with added lung, heart and especially muscle strength while you rest.

If you don’t remember, PACE stands for Progressively Accelerating Cardiopulmonary Exertion.

It draws on those larger muscle fibers, which generate more power. By exercising the larger fibers, you get stronger muscles that can handle heavy-duty demands.

Strengthening your muscles this way is the most important thing you can do to keep your mobility and independence as you get older.

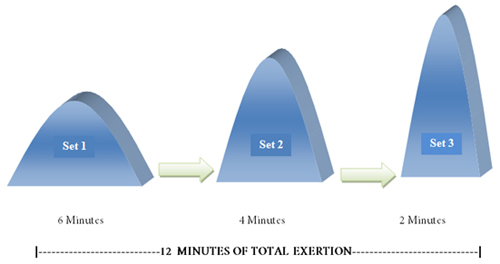

In the past few months, we’ve been doing some testing with PACE. What we’ve discovered is that the PACE principle works best when you do three sets of exercises.

The first is a warm-up set that lasts from 4-6 minutes. The second is a ramp-up set that should last for 4 minutes. You exert yourself to the point where you could still talk, but you’re out of breath.

The third is for peak exertion. It should only last from 2-4 minutes, and you should be pumping hard enough by the end that you could only grunt a word or two if you had to.

Challenging your peak this way — a little bit each time, followed by periods of rest — is what causes your body to adapt by adding muscle mass and cardiopulmonary capacity.

In between sets, you want to recover so that your heart rate is about 30 beats per minute above your resting rate. It will take only 30 seconds for some, and longer for others. But don’t worry how long it takes at first. Your body will progress as you get more fit.

This is one of the things that makes PACE different. You don’t time your recovery in strict intervals. You recover fully, and then challenge yourself again during the next exertion period.

We’ve also structured a system to make PACE even more powerful.

We discovered that if you do three sets for three days in a row, you can improve your fitness exponentially, and grow a stronger heart and lungs even faster.

I call it PACE3 (PACE cubed), and it brings PACE to a new level.

Here’s a representation of your daily workout (12 minutes):

The beauty of PACE3 is that it really comes down to just one minute of exertion — the last minute of the third set. Everything else you have done up to that point is just getting you ready to push yourself as hard as you possibly can for that one minute.

And that’s when your body starts adapting and growing to meet the challenge.

So, instead of running your muscles into the ground, try adapting your workout to PACE3 for stronger, healthier legs and more mobility at any age.

You just have to apply the basic PACE3 principles:

1. Work out to your target exertion level; then rest.

2. Allow your body to truly rest and fully recover between sets of exertion.

3. Aim to progressively increase the intensity as your fitness level improves.

4. Accelerate your fitness by dialing up the intensity a little sooner in each workout.

5. Keep your total exertion time to 12 minutes.

6. Work out for three days in a row; then rest on the fourth day.

One thing to remember is that the last word in the acronym for PACE is exertion … not exercise. That’s because “exercise” has negative connotations. We expect it to take a lot of time (and cardio training does take a lot of time).

We also get bored doing the same thing over and over again. Traditional exercise feels like a chore. And no one gets excited about doing chores.

So stop doing what bores you! PACE feels more like play. You can use any physical activity you choose, as long as it gets you pumping harder, not longer.

The focus is on that one moment in time when you challenge your peak of exertion — not on exercising for hours at a time. Your PACE workout never lasts for more than 12 minutes of total exertion, so you get more benefit in a fraction of the time!

Most Popular:

She Dropped 45 Pounds by Walking 45 Seconds

References

1 Newman, Anne B., et al, “Strength, But Not Muscle Mass, Is Associated with Mortality in the Health,” J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006; 61 (1): 72-77

2 Swallow, Elisabeth B., et al, “Quadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” Thorax 2007;62:115-120

3 Kamiya, Kentaro, et al, “Decreased Strength of Quadriceps Increases the Risk of Mortality…” Circulation 2010;122:A12709

4 Schuetz, Uwe, M.D., “Longitudinal Follow-up of Changes of Body Tissue Composition in Ultra-Endurance Runners…” Notes from 96th Mtg. of Rad. Soc. of N. America Nov. 2010; rsna2010.rsna.org